The Prince Albert National Park (PANP) is reporting population numbers of the Sturgeon River plains bison herd have dropped by many hundred since a recent peak around 13 years ago. However, it could potentially be on the rebound after seeing an increased number of bison calves.

According to information provided by the park, in 1969 around 50 plains bison from Elk Island National Park were brought to Central Saskatchewan. After that 10 to 15 of the Bison moved south and found a home in the Sturgeon River area in the Prince Albert National park, which has formed the herd there today.

The population grew and reached its peak between 2006 and 2008, which was 450 bison. Today it has declined to an estimated 120 animals.

Joanne Watson, resource management officer at PANP told paNOW an anthrax outbreak in 2008 was the beginning of the decline.

“We found 29 carcasses, we estimate there was probably around 60 individuals that were lost from the population due to that disease outbreak,” she said.

Watson added since the herd is wild, they’re not physically managed by humans which means predators such as wolves do prey on them. However, further study showed only the sick or weak bison were preyed on. She said predation doesn’t usually affect a population from growing.

Hunting females dented numbers

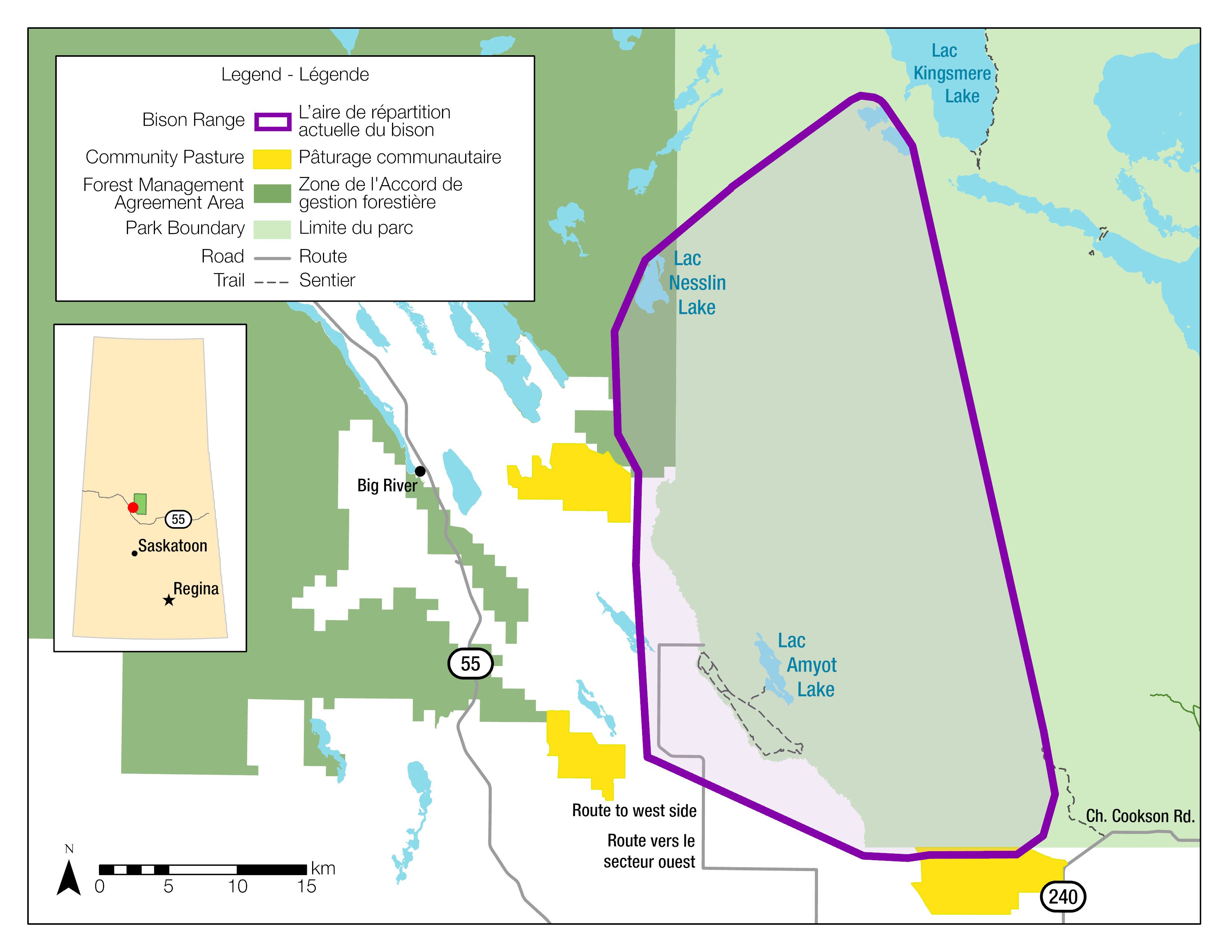

After looking into other factors, she said numbers continued to drop due to increased hunting of bison outside protected areas of the park. The herd would wander outside of the protected areas into farmland to feed.

“A number of years back harvesting rates were quite substantial, and we found that particularly breeding aged females were being harvested as opposed to other age classes or sexes of the population,” she said.

The purple line indicates the area plains bison are usually populated. Once they leave the park boundary they’re not in the protected area. (Submitted photo/Prince Albert National Park)

The purple line indicates the area plains bison are usually populated. Once they leave the park boundary they’re not in the protected area. (Submitted photo/Prince Albert National Park)She said through collaborative bison management between Sturgeon River Plains Bison Stewards, CPAWS, the Buffalo Guardians, Parks Canada, the Government of Saskatchewan, Indigenous communities, and local landowners they’ve worked together to bring down harvesting rates and manage the size of the herd.

Education and other strategies

“We’ve also pointed out to harvesters that maybe they should take males as opposed to females, that way they can help our breeding stock and try to help the population increase again,” Watson said.

The bison are still leaving the park, but she said it hasn’t been as often as in the past. While on the land, bison can do damage to cropland and fences.

To try and reverse the decline they’ve conducted prescribed fires over the last few years which help influence bison movement and replenish grazing habitat in the park. The animals have been noticed feeding on the new growth.

They’ve also built electric diversionary fences in the southwest boundary of the park along the Sturgeon River where the bisons most often wandered out of the protected areas. Preliminary data, she explained, showed that since putting up the fences the animals spent less time outside the protected areas on farmland.

She added there is an increased number of younglings in the Sturgeon River herd, which is a positive sign of growth. She explained they’re optimistic of future herd expansion.

An annual survey done in February counted 91 bison which is the highest in three years. Watson said aerial surveys give them a minimum population count because there are portions of the forest which are hard to see from the air. Because of that, some of the herd is not detected from the aerial survey and they’re working on doing more on-ground monitoring.

“Plains bison are known as ecosystem engineers, so that means they shape the landscape for all other plants and animals including anything from birds, insects, to predators,” Watson explained. “If we don’t have bison in our ecosystem, the ecosystem is essentially broken and can’t work as intended to. So that’s kind of the importance of conserving the bison and keeping them on our landscape.”

–

On Twitter: @iangustafson12